Digital

Tok Stori

A research project

In Melanesian pidgin languages, tok stori translates to ‘talk story’—storytelling

This research project explores the phenomena and significance of digital storytelling by Pacific peoples on social media through a Melanesian lens of 'digital tok stori' (digital storytelling).

Storytelling is an integral part of Pacific people’s identity and life and is embodied in the concept tok stori. Kabini Sanga and Martyn Reynolds’ describe the concept and methodology of tok stori as “a way of negotiating with the social world” and as “an everyday Melanesian discursive form of group communication that takes place when people interchange and exchange, creating a collective experience in which the development of relationships is both an accompaniment to, and a purpose of storying” (2019, p.12).

Tok stori is rooted in the Melanesian wantok system characterised by relationality and reciprocity. The word wantok, translating to ‘one/same talk,’ was born of “labourers from various Melanesian language groups working together on plantations” wanting to express connection to each other and communicate, and thus developed a creole language form (Sanga et al., 2018, p.6). Today, the wantok system is used to establish and acknowledge relationality between Melanesian peoples and “provides the basis for social interaction among actors that otherwise would have little in common” (Okole, 2005, as cited in Sanga et al., 2018, p.6).

Through a tok stori framework, digital storytelling occurs in an interactive digital space within online social networks—“virtual communities” (Rheingold, 1993). These communities could be considered different levels of wantoks connected by a relationship to a place, people, language, and cultural heritage, stretching from the village to regional connections.

Diverging from the dialogical nature of tok stori, yet grounded in tok stori’s underpinning values and principles of storying, relationality and reciprocity, I adapt and employ a framework of tok stori to interpret, conceptualise and recognise places of interaction and dialogue in the Pacific that extend beyond the oral form of storytelling. These include art, literature, film, photography, podcasts, and as observed here–multimedia visual forms of social media.

Project Overview

Presented in this space and adapted from my Masters research project is a snapshot of my research on how Pacific people (particularly Papua New Guineans) are harnessing the affordances and tools of social media to disrupt colonial narratives and representations of the Pacific by self-representing and reimagining contemporary Pacific identity.

This is done through a tok stori framework and the analysis of two Instagram accounts: @archiveples and @taniabphoto.

The analysis was then situated within the broader landscape of PNG and Pacific social media use, and a comprehensive literature review.

This research does not seek to define PNG identity but rather observe and make meaning of how both technologically and socially the dynamic and multifaceted nature of PNG identity is being articulated and reimagined in these spaces and this time.

Papua New Guinean viewers are advised that this research contains images of people who have died.

The Researcher

The Researcher

Inspiration

This research was inspired by both emerging Pacific content creators carving out space for and reimagining themselves and their community in the digital realm, as well as the literary waymakers in the Pacific who harnessed the tools of literature and publishing to reach wider audiences, self-represent, and reimagine themselves.

I wanted to highlight the significance of this phenomenon of digital tok stori in the face of long histories and legacies of negative colonial representations of the Pacific.

I also wanted to make the connection that digital tok stori is a significant technological progression of the storytelling, decolonising, and reimagining mediums of literature and art in the Pacific.

Inspiration

Intention

This website and linked Instagram is intended to give back, connect with and make my Master’s research visually and digitally accessible to the online communities researched.

To celebrate, uplift and acknowledge the work, innovation, and genius of Melanesian and Pacific content creators re-imagining our narrative.

I hope to provide greater visibility to their work and inspire others in the way that online communities and spaces have empowered and inspired me.

Intention

Welcome, my name is Angela Kampah Matthews. I was born in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville to the Baitsi clan of South Bougainville, PNG. I am also a 4th generation European-Canadian settler. I have lived largely outside of PNG in Australia and Canada since the onset of the civil war that displaced our family.

I graduated in the Pacific Studies stream of the Master of Indigenous Studies Programme at Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington.

Since living outside of PNG with minimal diasporic community, online digital spaces have been significant for staying informed and for identity development through feeling a sense of connection, reflection, community, and belonging with other PNG, Melanesian, and Oceanic people.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are given to content creators Samira Homerang, Lavau Nalu (of @archiveples) and Tania Basiou (of @taniabphoto) for allowing me to research the digital tok stori occuring in their digital spaces.

Thank you to Dr. April Henderson for her supervision and guidance.

Thank you friends that helped me with revisions and edits.

A Note on Terminology:

The terms Pacific, Pacific peoples, or Oceania in this research project are in reference to people with Indigenous ties to land in the Pacific regions of Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia, be they living in their homeland or abroad, and includes Māori.

I use Indigenous to refer to peoples with recent Indigenous ancestry and connection to land and acknowledge that Papua New Guineans may not identify as Indigenous as it is subjective and context dependent. Debates on how Indigenous is used in the Pacific are developing (Clifford, 2007; Thaman, 2003, p.8).

I use the terms modern and modernity in a way that challenges the Eurocentrism embedded in the terms and instead recognise that “different communities, countries, and regions produce different modernisms at different times” (Hayward & Long, 2020, p.9).

Tania Basiou of @taniabphoto explains:

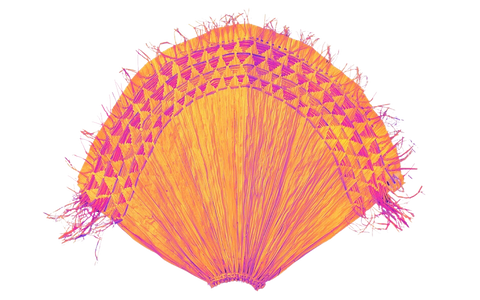

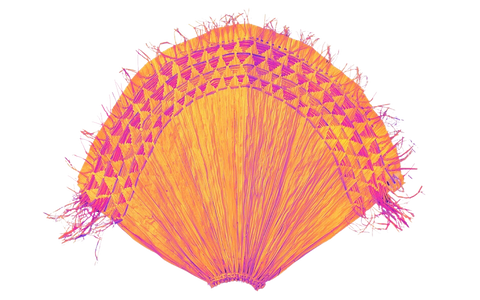

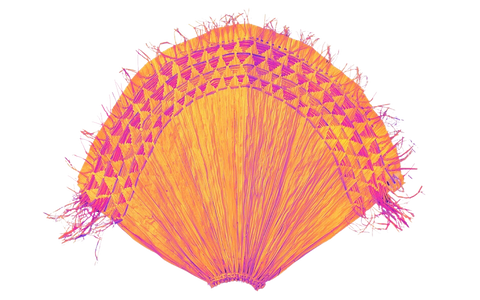

"The Biruko fan is made by the women of Central Bougainville.

Its journey begins when the young palm leaves that have yet to unfurl, are cut and boiled and laid out to dry in the sun. The pieces are then carefully matched and layered, and sewn together with a thin string made of bark. Finally, colourful designs are threaded through the biruko, with wool. These designs are inspired by patterns seen in nature—mountains, waves, fishbones etc.

While the Biruko fan has many uses, you will most often see the women dancing with them at singsings. They are also gifted along with karamani (pandanus mat) and tora (work sacks), at cultural ceremonial exchanges or to mark rites of passage.

The decorative birukos make great display pieces or are used as fans.

Plain fans serve more practical purposes ranging from an umbrella to a makeshift mat for mothers to lay their babies on"

The women of our region make the Biruko fan. I chose to use the image of the Biruko fan in this research project as a metaphor and representation of the non-dialogical form of tok stori (storytelling) explored in this research. Like the social media explored here, the Biruko fan can have many uses and is a visual form of storytelling in the way it is used in cultural dances and in the ways messages can be sewn into the fan when gifted. It also embodies the underlying values and principles of tok stori: storying, relationality and reciprocity. Its use as a mat or umbrella also lends to tok stori being a framework that guides, protects, and holds this research.

A Note on the Image of the Biruko Fan

The digital space is a technological progression of the reimagining and decolonising mediums of literature and art.

This flourishing reclaiming of control to self-represent and re-construct our identities, narratives, and representations of the Pacific heeds the calls to awaken to colonial legacies, to reimagine ourselves, and to no longer be caged in the ways we have been imagined for centuries by ethnocentric oppressive others—be that through reductive colonial narratives or current mass media (Hau‘ofa, 1998).

Hau‘ofa’s call still travels into the digital media age, as younger generations of Pacific peoples act in digitally subversive and reimagining ways on the digital frontier of Pacific people’s world enlargement (Hau‘ofa, 1994).

Tenkiu

Thank you